2022 Strikes 1: Çimsataş Strike

Çimsataş (Çukurova Construction Machinery Industry and Trade Inc.) is an industrial company of Çukurova Holding based in Mersin. Started in 1972, the company's headquarters and factory are located in the Akdeniz district of Mersin, on the Tarsus road. Çimsataş produces raw and machined, hot forged and steel casting parts for construction machinery, automotive, railway and agricultural machinery manufacturers in Turkey and Europe.[1] Çukurova Holding, to which Çimsataş belongs, was founded in 1923 by Mehmet Kemal Karamehmet in Tarsus.[2] Mehmet Emin Karamehmet, the chairman of the board of directors of Çukurova Holding, one of the largest conglomerates in Turkey, is ranked 48th in the list of Turkey's 100 Richest People and Families for 2023 by Ekonomist Magazine.[3]

MESS and Group Collective Bargaining Agreement System

Çimsataş, is a member of the Metal Industrialists‘ Union of Turkey (MESS) which is the biggest bosses’ union in the metal industry. The importance of MESS for the metal bosses operating in Turkey, of which many companies such as Oyak-Renault, Ford, Arçelik, Erdemir and Tofaş, which are in key positions for the industry of Turkey, are members, dates back to the 1960s, when a mass and militant labour movement was on the rise. Founded by 11 bosses with the name ‘ Mineral Goods Industrialists’ Union‘ under the leadership of the Koç Group, MESS represents a portion of the Istanbul-based industrial companies of the period.[4] Although MESS was founded on 14 October 1959, like other bosses’ unions, it was only after the Collective Bargaining, Strike and Lockout Law No. 275 entered into effect on 24 July 1963 that it was able to conclude collective bargaining agreements on behalf of its members in the metal industry. Article 7 of Law No. 275 authorised bosses' unions to conclude collective bargaining agreements on behalf of the bosses who were their members.[5] On the other hand, in parallel with the gradual growth of the “metal manufacturing sector”[6] in the 1960s, which included all mines and steel industry, metal goods, machinery manufacturing, etc., and the increasing importance of these sectors in the capitalist production process in Turkey, a young and militant generation of workers emerged in this sector and led to many strikes. This situation has made the group collective bargaining system, and thus MESS, indispensable for metal bosses since the 1960s. At a time when neoliberal policies were being implemented, the metal sector was of critical importance for Turkish capitalism.The fact that Turgut Özal, one of the architects of the famous 24 January decisions and one of the symbolic names of the neoliberal policies put into effect after 1980, served as the general secretary of MESS between 1977-1979 is an expression of this.

At the 10th General Assembly of MESS in 1970, a boss named Mustafa Evirgen complained: "They are so well organized; they sit down, they do not even destroy, they just go to the toilet, the worker doesn't come out in half an hour. He says he has a colic, write a medical visit form, let him go to the doctor. The queue doesn’t end until the evening. In other words, they use all the weapons to reduce work efficiency so well that we are all helpless in the face of them."

Another said the following: "I went home late last night. When I was explaining the reason to my wife, I said, ‘Tomorrow our workers are going on a sit-down strike’... 'There is nothing about us. In another factory in our sector, the employer changed a manager and the workers reacted against it. They created a de facto situation. The employer suspended the factory temporarily. They gathered, in all the workplaces in the sector in those districts... and decided on a one-day sit-down strike. The law forbids sympathy strikes, but not sit-down strikes,' I explained. 'So what are you going to do,' she said. I said, 'We will prepare lunch for our workers and we will have their cars ready for them to return home'."

As a result, from the early 1970s onwards, MESS adopted collective bargaining agreements at the group level as a basic principle as a way to contain rising labor movements. In this way, it was aimed to prevent workers from imposing their demands on the bosses individually through strikes, occupations and other effective collective actions that they could carry out in individual workplaces.[7] On the other hand, the metal bosses wanted to create a wage hierarchy in the workplace through wage grouping.

The Role of Trade Unions in the Group Collective Bargaining Agreement System

A group collective labour agreement is basically a type of collective labour agreement. However, group collective bargaining agreements are signed between labour unions and employers' unions of which bosses are members, covering more than one workplace in a line of business. As defined in Article 2 of Law No. 6356 on Trade Unions and Collective Bargaining Agreements, a group collective labour agreement is an agreement between a trade union and an employers' union covering workplaces and enterprises in the same line of business belonging to more than one member employer.

Beyond the individual interests of the bosses, the collective struggles of the workers in the metal sector are important for the whole of capitalism due to the role of the sector in the economy of Turkey, its connection with different sectors and the fact that international capitalist monopolies such as Renault, Ford and Siemens operate in this sector. On the other hand, there is a direct relationship between the main industrial companies and the sub-industry companies that produce spare parts and materials. The wages of workers in sub-industry companies affect the profitability not only of the sub-industry company but also of the main industrial companies to which these companies supply products. The main reasons for sub-industry enterprises to be made a component of group collective bargaining agreement instead of independent collective agreements are the desire to standardize “labour costs” at the sectoral level and, in parallel with this, the fact that the costs of sub-industry[8] enterprises are directly reflected on the costs of the main industry. For this reason, the aforementioned group collective bargaining agreements prevent individual workers from entering into collective bargaining agreements with their bosses, and instead, a single agreement is prepared that regulates wages and other rights in all MESS member workplaces.

The other cog that keeps this wheel turning is the trade unions that negotiate with MESS on behalf of the workers. According to the Communiqué dated 24 July 2024 on the July 2024 Statistics on the Number of Workers and Members of Trade Unions in the Trades Unions, there are 295,192 members of Türk Metal Union, 47,287 members of Özçelik-İş and 38,834 members of Birleşik Metal-İş, which are the authorized trade unions in MESS member workplaces. As a result of the negotiations between the three trade unions and MESS, a single contract covering all workplaces is signed. The Türk Metal Union, of which 14.81 percent of workers in the metal sector are members and which is authorized in the largest workplaces in the sector such as Arçelik, Oyak-Renault, TOFAŞ and Ford, is the most important partner of MESS in this system. Although the leaders of Birleşik Metal-İş make speeches in every contract period that they will not accept the conditions imposed by MESS and that they will strike if necessary, in the end all unions sign the same contract. Even if the reason given for this situation is that the Türk Metal Union is authorized in most of the workplaces in the main industry and therefore has a decisive position in the contract, this does not change the fact that Birleşik Metal-İş (and of course Özçelik-İş), instead of striking, often signs contracts that its member workers do not agree to.

It should be emphasized that the dominance of the Türk Metal Union in the sector did not happen by chance, but through the direct intervention of the state and the bosses. Following the September 12 military coup, Türkiye Maden-İş was shut down, many workplace representatives were detained or fired, strikes were banned, and the bosses and the state began to establish the dominance of Türk Metal in the workplaces. In many workplaces, especially those where Türkiye Maden-İş was authorized, workers were literally forced to become members of Türk Metal at the point of a bayonet.

Under these conditions, it becomes almost impossible to organize an official strike in MESS member metal workplaces. After September 12, the only instance in which collective labour negotiations between MESS and labor unions resulted in an effective strike was the 1990-91 MESS strike, which took place at a time when a new wave of labor movement was emerging. The strike, which started due to the lack of results in the collective labour agreement negotiations conducted by Otomobil-İş[9] and Türk Metal Unions with MESS on behalf of 85 thousand workers working in 230 workplaces, lasted for 30 days.[10]

After this date, there were no strikes in the collective labour agreement processes with MESS, except for a one-day strike by Birleşik Metal-İş in 2015. On September 1, 2014, Çelik-İş[11] and Türk Metal Unions reached an agreement with MESS and signed the Group Collective Labor Agreement covering the years 2014-2017.[12] However, no agreement was reached in the group collective labor agreement negotiations between Birleşik Metal-İş and MESS, and the union decided to strike at 20 workplaces on January 29, 2015 and 18 workplaces on February 19. The strike at 20 workplaces actually started to be implemented on January 29, but the Council of Ministers decided to postpone the strike on January 30 on the grounds that it was "detrimental to national security."[13] The "postponement", which we have seen many examples of in Turkey, practically means the prohibition of the strike. As per Article 63 of the Law No. 6256 on Trade Unions and Collective Labor Agreements,[14] which at the time authorized the Council of Ministers to postpone a legal strike that had been decided or started, if an agreement could not be reached between the parties through a mediator within 60 days of the postponement period, the union had no chance to re-implement the strike and had to apply to the Supreme Arbitration Council in order not to lose its collective labor agreement authorization, and the decision of the Supreme Arbitration Council was binding. Ultimately, after the postponement, the Supreme Arbitration Council decided on 12 May 2015 that the Collective Labor Agreement for the workplaces where Birleşik Metal-İş is authorized will have the same conditions as the Group Collective Labor Agreement signed with the other two unions.[15]

Metalworkers' Tradition of Struggle

After September 12, under the conditions we have been talking about, it became practically impossible to organize an official strike. And the unions, as part of the collective labour agreement system, functioned as nothing more than a means of keeping workers under control. Nevertheless, metalworkers have a deep-rooted dynamic of struggle. The most important and militant examples of rising workplace struggles from the 1960s to 1980 were in the metal and mining industries.

The wildcat strike in 1963 at the Kavel Cable Factory -founded in the early 1950s by Vehbi Koç, one of Turkey's leading capitalists- is one of the most well-known examples of this period. After Kavel, the first collective labor agreement negotiations between Türkiye Maden-İş and MESS ended in disagreement, leading to a wave of strikes known as the 1964 MESS strikes. Strikes began on June 11, 1964 at the Adapazarı Agricultural Equipment Corporation factory, on July 31 at the Ayvansaray Cıvata Factory, on August 10 at the Arçelik Factory and the Neşet Dever Metal Goods Factory, on August 11 at the Sungurlar Boiler Factory, on August 17 at the Emayetaş Metal Goods Sheet Metal and Enamel Factory, and on August 24 at the Altınbaş Nail Factory.[16]

In 1977, after the collective labour agreement negotiations covering 63 workplaces where Maden-İş was organized ended in failure, the "Great Strike" that started on 30 May 1977 in 25 workplaces was the biggest strike wave that the metal industry had witnessed up to that time. Together with the 7 strikes started in 1976, strikes were implemented in 32 workplaces where Maden-İş was authorized in the same period. In 12 workplaces where a strike decision was taken, lockout was declared by MESS before the strike was launched, and the strike was broken in 2 workplaces in the following period. In the first days of 1978, the collective labor negotiations between Maden-İş and MESS resumed and resulted in an agreement on February 3, 1978. With this agreement covering 63 workplaces; strikes and lockouts in 42 workplaces were lifted. The agreement was described as a “victory” by Maden-İş.[17] At this point, it is noteworthy that the resumption of the negotiations between MESS and Maden-İş and the conclusion of the strike by reaching an agreement in these strikes called the Great Strike, took place after the 6th General Assembly of December 22-29, 1977, when the influence of the TKP within DİSK was broken and DİSK was completely under the control of the CHP.

Shortly after the signing of the protocol ending the Great Strike, the metal industry witnessed a new wave of strikes. After the collective labor agreement negotiations between Maden-İş and MESS on behalf of more than 5,000 members in 21 workplaces ended in a dispute, Maden-İş first decided to strike in 15 workplaces in May 1978, in accordance with the legal deadlines. The second wave of strikes was launched gradually in 8 workplaces within the context of the dispute. The strikes ended with an agreement on July 31, 1978. Maden-İş declared that the collective labor agreement was “concluded with the highest level of agreement in the sector and the strikes ended with victory.”[18]

On March 13, 1980, 4 thousand workers went on strike in 12 MESS-affiliated workplaces where Maden-İş was authorized. In line with the decision taken by Maden-İş, another 40 workplaces went on strike on March 19 and by mid-April the number of workplaces on strike reached 60 and the number of striking workers reached 22 thousand. On April 7, 1980, the collective labor agreement negotiations between Otomobil-İş and MESS for 14 workplaces ended in a dispute. In September 1980, 30 thousand workers were on strike in 74 workplaces affiliated to MESS. The MESS strikes were banned, along with all strikes, by the National Security Council's (MGK) September 14, 1980 declaration issued after the September 12, 1980 military intervention. In some workplaces, workers resisted by not going back to work for another day. However, on September 16, work resumed in all workplaces.[19]

After September 12: Metal Workers' Struggles

After being suppressed by September 12 Coup, workers' protests were on the rise again, especially in the late 80s and early 90s, and important struggles took place in the metal sector workplaces. The first major strike of the post-September 12 period, that of NETAŞ workers who were members of Independent Otomobil-İş, which started on November 18, 1986 and ended on February 18, 1987, is one of the most important examples of this. In the 1989 Spring Strikes, workers at the MKE Kırıkkale Factory, where Türk Metal was authorized, and the Karabük and İskenderun Iron and Steel factories, where Çelik-İş was authorized, also participated.[20]

The 1990-91 MESS strikes mentioned above are also one of the important struggles that took place in the metal sector after September 12. However, after this date, all of the strikes in MESS member workplaces took place without unions, despite unions, and in some cases against unions. The first of these took place in 1998 in factories where the Türk Metal Union was authorized. At that time, in the collective labor agreement negotiations between MESS and the unions of Türk Metal, Birleşik Metal-İş and Özçelik-İş, workers were expecting a raise of at least 90 percent. However, in the middle of the night on September 17, the unions, without the workers' knowledge, signed an agreement that called for a 43 percent increase for the first six months and an inflation rate increase for the following period. This contract, which was signed without their knowledge, unleashed the anger that had accumulated among the workers in the factories where Türk Metal was authorized, starting from Bursa.

The first action in this process took place at the Oyak Renault factory in Bursa on Friday, September 18. The workers who came to work in the morning shift started a wildcat strike by not going to work. Around 3,500 workers gathered in the factory yard and chanted slogans protesting the union. Later, the workers brought a notary to the Organized Industrial Zone where the factory was located and started to resign from the union en masse. While the strike by Renault workers continues, Mako, Bosch, Karsan and Siemens workers also take action. At 14:00, 700 workers at the Bosch factory marched with slogans to the No. 1 branch of the Türk Metal Union to protest against the union, but they could not find an interlocutor. In the following hours, about 2,500 Mako and Bosch workers marched to the front of the Renault factory and joined the workers there. The boss of Oyak Renault, on the other hand, decided to suspend the factory for two days in order to end the action. That day, the protests in front of Oyak Renault continued until 22:00.

At the TOFAŞ Automobile Factory, workers on the morning shift also go on strike and block the Bursa-Yalova highway for a while. Following the announcement that the factory at Tofaş would be closed for two days, around 3-4 thousand workers marched on the ring road to resign from the union en masse. After Bursa, workers at the Ford Otosan factory in Istanbul began a strike at 14:45.[21]

On Monday, September 21, protests and union resignations spread to many factories in Bursa, Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. Workers at Renault, Tofaş, Mako, Coşunöz, Bosch, Valeo, Delphi Packart, Döktaş, Otosan, SKF, BMC, Uzel, Teknik Malzeme and Çerkezköy AEG factories resigned en masse. In many factories such as Renault, Tofaş, Mako and Bosch, workers went back to work on Monday. On the other hand, Bosch, Coşkunöz, SKT and Döktaş workers in Bursa and BMC workers in İzmir stopped production and resigned from the union en masse. Manaş workers in Ankara also stopped production and blocked the Ankara Esenboğa Airport road for a while. Uzel Makina workers in Istanbul gathered in front of the factory to protest against the union.

However, there were no long-lasting strikes in the factories. This is because the workers' main goal is to get rid of Türk Metal. For this reason, they organize strikes that are limited to ensuring that they are not prevented from resigning and do not exceed one day. In many workplaces, workers resigned without disrupting production at all or disrupting it for a short period of time by going to notaries outside of working hours. In the face of such a mass outburst of anger, the bosses do not take an attitude to prevent the resignations in the first place. On the contrary, in many workplaces, managers make speeches to workers that they have the freedom to choose their union. In the BMC factory, managers even promised 10-20% additional raises to the protesting workers.[22]

As a result, approximately 9 thousand workers resigned from Türk Metal in a very short period of time. However, after the initial reaction, Türk Metal, MESS and company executives began to pressure workers with threats of dismissal in order to prevent resignations from the union and to ensure that those who resigned would become members again. The Istanbul Anatolian Side Branch of the Türk Metal Union distributes a leaflet in the workplaces threatening workers who resign. The leaflet openly threatens workers who resign from the union with the statements “Working conditions in the workplaces will become even harsher, the most severe punishments will be given for the smallest incident, arbitrary dismissals will begin, and the CLA [Collective Labour Agreement] will not be utilized for 24 months”. Shortly afterwards, mass layoffs began in the workplaces. Around 300 workers were dismissed at Tofaş and around 20 at Oyak Renault. Eventually the resistance of the workers was broken and Türk Metal regained control.

In 2012, the anger of the workers in the metal industry against Türk Metal was again exposed. Türk Metal's proposal for an 18% raise in the collective labour aggreements led to a new wave of protests in many factories. Workers at the BMC factory in Izmir, the Eskişehir Arçelik factory and the Otokar factory in Sakarya organized protests against the union. At Oyak Renault, workers on the evening shift on November 13 refused to leave the factory and went on strike. The next morning, as Renault workers gathered in the factory courtyard at shift change time, workers from the Bosch plant were attacked by unionists from the Türk Metal Union. Three workers were injured in the attack using cleavers, and 22 workers were fired after the protests.[23]

2015 Metalworkers’ Strikes

In 2015, the biggest and most effective wildcat strike wave ever experienced in the metal sector took place in the workplaces where the Türk Metal Union is authorized. The wildcat strike, which started in May at the Oyak-Renault factory in Bursa, quickly spread to dozens of factories authorized by the Türk Metal Union in Bursa, Eskişehir, Ankara, Kocaeli, Gebze, Çerkezköy and İzmir.

The process that triggered this strike wave dates back to the authorization dispute between Türk Metal and Birleşik Metal-İş at the Bosch factory, which has been ongoing since 2012. During the contract period, the dispute over authorization was taken to court and the court case, which lasted for nearly 2 years, was concluded in favor of the Türk Metal union in 2014. After Türk Metal was authorized in the workplace, Bosch workers, who had not received a raise during the court process, were given a raise above the MESS group agreement valid for other factories. Thus, it was aimed to suppress the anger of Bosch workers, who had already resigned from the union, against the union and to prevent them from resigning from the union again. As a result, when it became known in other factories where Türk Metal was organized that workers in the Bosch factory had received a relatively higher hourly wage increase for the 2012-2014 period than other factories in the group, reactions started and this triggered a strike.[24]

The announcement of this situation caused the anger that had been accumulating for years against Türk Metal, which had signed contracts under miserable conditions, to come out in a strong way. After the signing of the collective labour agreement at Bosch, workers at the Oyak-Renault factory, which has a strong tradition of struggle, began to grumble and react with different forms of action. Renault workers staged various actions inside the factory starting on April 14, and on April 22, the words of Ruhi Biçer, the head of the Türk Metal Branch, to the workers who reacted against him, “If I sold then I sold well, then I was a good pimp,” further increased the anger.[25] Under the influence of this attitude, the 24:00-08:00 shift did not get on the shuttles after work and gathered in the courtyard. The workers were prevented by the police from marching to the PTT to get their e-government passwords so that they could resign. They then decided to instigated a dunning letter to the union on Friday, April 24 to demand a new contract in line with their demands and to hold a demonstration on Sunday, April 26 at Bursa City Square, to which all workers would be invited.[26]

On April 26th, in addition to Oyak Renault workers, Coşkunöz, Mako, Ototrim, SKT and DJC workers also participated in the demonstration at Bursa City Square. There, the workers openly showed their reaction to Türk Metal with slogans such as “Türk Metal Must Resign” and “We Don't Want a Sellout Union.”[27] The union did not take any positive steps in the time given by the workers to Türk Metal until May 5. Thereupon, on May 4, Oyak Renault workers left their 08:00-16:00 shift and gathered in the garden of the BTSO Organized Industrial Mosque. Renault workers were joined here by Coşkunöz, Mako and Ototrim workers coming off the same shift. The workers make a statement here, announce that they will meet the next day and resign en masse, and end the action by agreeing to meet at the same place in the morning after their shift.[28]

On May 5, when the deadline given to Türk Metal expired, workers gathered at the same place and started to resign from the union through the e-government application using the computers on the tables set up in the area. As the workers queued up in front of the resignation desk, Türk Metal members waiting around entered the area and attacked the workers and members of the press. A reporter and an Oyak Renault worker were injured in the attack.[29] Workers had been entering and leaving the factory en masse for some time. On the night of May 5 to May 6, workers who were going to work the 24:00-08:00 shift gathered at the factory entrance. As they expected, some workers' cards were not recognized. Then, as they had previously decided, the workers outside did not go inside, the workers whose shift was over did not come out, and production stopped.

After this strong reaction of the workers, the managers came to the factory around 02:00. As a result of the negotiations, Renault management had to back down and take back the dismissed workers. During the negotiations, the company executives promised not to interfere with the workers who would resign from Türk Metal, and asked for time to negotiate with France on wage improvements. Workers give management until May 22. At around 03:30, the 24:00-08:00 shift starts work.[30]

On the morning of May 14, MESS made a statement saying "It is not legally possible to grant additional rights to the terms of the 3-year Group CLA, which is binding for the workplaces covered by it in accordance with the legal procedure and collective bargaining order. For this reason, it is necessary not to have different expectations and to avoid illegal behaviors that will cause disruption of the working order in the workplace by getting caught up in provocations.” On the same day, Renault's General Manager told the workers working the 08:00-16:00 shift that it was not possible to amend the contract and that there would be no additional raises until 2017, the end date of the contract.[31] Following this statement, the workers decided to go on strike until their demands were accepted and started a wildcat strike by occupying the factory.

On May 14th, after Oyak Renault workers went on strike, strikes also took place in large factories such as Tofaş, Coşkunöz, Mako, Ototrim, Ford and Türk Traktör. Following these strikes, a wave of independent strikes at different times in workplaces where Türk Metal is organized continued until the end of July, with aftershocks lasting until September. As a result, from May to September, wildcat strikes of varying duration took place in around 30 factories employing around 50 thousand workers, and there were mass resignations from Türk Metal.

As the strike and protests spread to different factories, an agreement was reached between the workers and the company management at Oyak Renault, where the strike wave began on May 27. In Renault, where numerous negotiations were held throughout the strike, a nine-article agreement was reached at the end of the negotiations held on the night connecting May 26th to the 27th, and the workers ended the strike and went back to work on the morning of May 27th.[32] As a result, the 13-day strike at Oyak Renault ended, but afterwards, both in Renault and in dozens of other factories where Türk Metal was authorized, workers' efforts to get rid of Türk Metal continued with mass resignations on the one hand, and strikes and symbolic actions on the other. In the end, within the scope of this strike wave, struggles took place in dozens of factories at different times, durations and forms, some of which resulted in partial gains and some of which resulted in no gains, over a period of about 3 months.

Struggles of Metal Workers after the 2015 Strikes

After the 2015 metalworkers' strikes, there have been numerous official or wildcat strikes in the metal sector. Around 1,600 workers at the Ortadoğu Rulman Sanayi (ORS) factory in Ankara's Polatlı district went on a wildcat strike on August 26, 2015, stopping production again on the grounds that the factory management had “failed to fulfill the promises it had made to the workers” during the 2015 metalworkers' strikes.[33] Due to its demands and the fact that ORS was one of the workplaces involved in the wildcat strike wave, this can also be considered as an aftermath of the wildcat strike wave that began in May.

Workers at the Gamak Motor factory in Dudullu, Istanbul went on strike on October 15, 2015, after collective labor agreements negotiations between the Çelik-İş union and the company ended in dispute. Following negotiations between the union and the company management, the strike ended with an agreement on December 8, 2015.[34]

A strike began on October 17, 2016 at the Cem Bialetti factory in Kartepe district of Kocaeli, which produces cookware. As a result of the negotiations, the strike ended with an agreement on October 20 after the employer offered a 21 percent raise excluding social rights.[35]

On December 8, 2016, a strike started at the Bekaert İzmit Çelik Kord Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. factory, which produces industrial steel wire in İzmit, due to the failure to reach an agreement during collective labor agreement negotiations between Birleşik Metal-İş and the company management. The strike was ended on December 22, 2016 as a result of the agreement reached.[36]

The strike, which started on January 20, 2017, was postponed by a decision of the Council of Ministers following the failure to reach an agreement on the group collective labor agreement between the Birleşik Metal-İş Union and the Electromechanical Metal Employers' Union (EMİS)[37] covering 2200 workers. Workers at GE Grid Solution, ABB Electric, Schneider Energy and Schneider Electric, which are members of EMIS, actually continued the strike. As a result of the workers' actual will to strike, the union announced that a meeting will be held on Monday, January 23rd to decide whether the strike will continue or not. In a statement released by Birleşik Metal-İş, it was announced that an agreement was reached to raise hourly wages by 1.20 liras plus 7 percent for the first six months, ending the strike. Prior to the strike decision, the employer union EMİS had offered a wage increase of 1.10 TL plus 7 percent for the first 6 months, inflation plus 2 percent for the second 6 months. Birleşik Metal-İş Union, on the other hand, had demanded a 2 liras plus 12 percent increase from the employer. Thus, the agreement was signed with an hourly wage increase of only 10 kuruş(cents) more than EMIS' offer. After the strike, 29 workers at Schneider Elektrik were dismissed on the grounds of “downsizing.”[38]

On July 31, 2017, workers at Tekno Maccaferri in Düzce, members of Birleşik Metal-İş went on strike. The 57-day strike ended with an agreement.[39]

Workers at the Cem Bialetti factory in Kartepe went on strike on May 7, 2019 after the United Metal-İş Union and the employer failed to reach an agreement during collective bargaining agreements. After 14 days of strike, the strike ended with an agreement on May 21 after the boss accepted a 620-TL net wage increase.[40]

On March 9, 2021, workers went on strike at the Cem Bialetti factory in Kocaeli, which manufactures kitchenware and employs 61 workers, after failing to reach an agreement during collective labor agreement negotiations and subsequent mediation process. The strike ended on March 27, 2021 after negotiations.[41]

The strike that started on December 25, 2020 at the Spain-based Baldur Süspansiyon factory in Çayırova district of Kocaeli, concluded with an agreement reached on 04.10.2021.[42]

Workers on the morning shift at Xiaomi Salcomp, a Chinese-owned company employing around 800 workers, staged a wildcat strike demanding recognition of their union rights.[43]

About 120 workers of Mitsuba Otomotiv factory in Gebze, Kocaeli, occupied the factory and went on a wildcat strike on October 11, 2021, after 9 workers were dismissed after they joined Birleşik Metal-İş union. On October 12, the strike ended after Mitsuba management accepted the union's authorization and agreed to begin collective labor agreement negotiations. Mitsuba management also announced that it would not reinstate the dismissed 9 workers, but promised to pay their compensation.[44]

Background of the Çimsataş Strike

The last months of 2021 were a period when the effects of the economic crisis in Turkey became more and more visible. The dollar exchange rate exceeded TRY 9 by October 11, 2021 and 10 by November 12, 2021. On November 23, 2021, also known as “Black Tuesday”, the dollar first reached 12 and then 13 TRY. Despite the Central Bank's interventions, the dollar exceeded 14 TRY on December 14, 2021 and then 15 TRY on December 16. On December 17, it first exceeded 16 TRY and later 17. On December 20, 2021, the dollar exchange rate reached a historical record of 18.36 TRY. The government tried to slow down the depreciation of the Turkish lira by introducing the so-called “currency-protected deposit system”, which requires the payment of the difference if the Turkish lira held in time deposit accounts increases more than the interest rate against the dollar, euro or sterling at maturity. In parallel with the depreciation of the Turkish lira, the increase in the inflation rate accelerated from October 2021.[45] Although there are comments and analyses that the announced data is below the actual inflation, as of October 2021, the Statistical Institute of Turkey (TÜİK) announced that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased by 13.58 percent in December compared to the previous month, and increased to 36.08 percent on an annual basis. Thus, annual inflation rose to the highest level since September 2002.[46]

Faced with the rapid decline in workers' real wages in the face of high inflation, the government increased the minimum wage by 35 percent from 2,825.90-TL net in 2021 to 4,253.40-TRY, effective from January 1, 2022. While this was the highest rate of increase in the minimum wage under AKP rule, with the increase to be made in July 2022, the total increase of 49 percent in the minimum wage reached the rates of increase during the Gulf Crisis and the 1994 crisis.[47] Although we can say that this rate of increase protected the purchasing power of minimum wage workers in the face of high inflation to some extent, the rate of increase was not reflected on those earning above the minimum wage. On the other hand, it has reinforced the expectation that all workers will receive a high increase in their wages, which are eroding due to high inflation.

It was under these circumstances that the MESS Group Collective Labor Agreement negotiations between the Metal Industrialists' Union of Turkey (MESS) and the unions of Türk Metal, Birleşik Metal-İş and Özçelik-İş -which determine the financial and social rights of 140,000 metal workers for the period between September 2021 and September 2023- began on October 12, 2021.[48] From the accounts of Çimsataş workers, we understand that the demands of the workers were not voiced at these meetings and that the signed increase rates were in fact approximately known beforehand.

Mehmet Kurt, the chief workplace representative at Çimsataş at the time, says the following in an interview published on Umut-Sen TV youtube channel:

"We went to MESS meetings. We attended the meetings in Istanbul, five of them. There we saw the position of the MESS group and what they wanted to do. We told our friends on the way back. The workers had a certain demand. I am a worker, after all, I also have demands. We told these demands to the general president at the central representatives meeting in December. I conveyed them to him there. I conveyed to him there that we would not accept these demands, that the requested raise rates were not enough, that it needed to be revised. Nothing changed."[49]

At the meeting held at Birleşik Metal-İş, the Çimsataş workplace representative's speech in which they demanded that the draft be revised

Çimsataş worker Mustafa Yalçın says the following in an interview published on the Evrensel youtube channel:

“Reactions started to rise in September. We pressured the chief representative and other representatives wherever they went, and at the general assemblies we told them that this draft was inadequate, that the work was good, but that the workers were in a bad situation, that they were constantly in debt. There was no response from there. Then the general president [Adnan Serdaroğlu, general president of Birleşik Metal-İş] came to the factory. There was also a reaction against the general president.”[50]

Mustafa Yalçın explains the reaction against Adnan Serdaroğlu in an interview on Umut-Sen TV youtube channel as follows:

"Adnan Serdaroğlu came to the factory. He said he would visit all the shifts. He saw only one shift. He realized that there was a lot of reaction from the people, so he left immediately. We heard from friends that he said the draft could not be revised. When the chairman came, he didn't know that there was no tea break. Someone says, 'We don't even have a tea break, Mr. President.' 'What, there is no tea break here?' he said. People experienced a shock there. After the reaction, he left without seeing the other shifts."[51]

In Halil İmrek's article titled "Çimsataş Resistance from the Words of the Workers" published in Evrensel Newspaper, the following statements of a worker are given:

"The demands of the workers and the demands of the CLA committee were never included in the draft. We asked for a 55 percent rate, and we had discussions with union experts. We objected to an understanding of keeping the raise rate low by saying let's keep the success rate high, we said this understanding would benefit the employer. They said let's ask for 30 percent this term, and the draft was already 30.8 percent. The men had already predetermined it. And they "supposedly" asked us. If you ask them, they would say the workers gave their consent.[52]

Finally, despite all objections, after four months of negotiations, the MESS Group Collective Labour Agreement for the period between September 2021 and September 2023 was signed by all three labour unions on January 12, 2022 at 02:30 in the morning. According to the signed CLA, it was decided to increase everyone's hourly wages by 10 percent for the first 6 months, with a 3.70 TRY diluted increase on top of that. Accordingly, it was announced that an agreement was reached to increase the hourly wage by an average of 27.44 percent for the first six months and 30 percent for the second six months in all workplaces covered by the agreement.[53]

When the news of the signing of the CLA came, Çimsataş chief representative Mehmet Kurt, who was in the union room of the factory with other workplace representatives and branch president Deniz Ilgan, was asked what they thought : “27.44 percent is not acceptable to this worker. We don't accept it either. Because the same money goes into our pockets,” he said. Although the 27.44 percent raise, which is far below the inflation rate of 36.08 percent according to the Statistical Institute of Turkey (TÜİK) and the 35 percent increase in the minimum wage, is the main reason for the reaction at Çimsataş, workers say that this is not the only issue.

Mustafa Yalçın says the following about the problems and the reasons for the outbreak of the wildcat strike:

"Actually, what happened at Çimsataş was not something that happened out of the blue. In the past, these contracts were bad, they were always signed at midnight. For example, I didn't see it, they are talking about the 2008-2010 contract. People were prepared to go on strike, but somehow the union prevented it by holding a meeting in the cafeteria and bringing the employer and workers face to face. In the 2014 contract, we also went on strike. The government prevented that strike too. We went back to work. The contracts after that were always below expectations. There are also human working conditions. We work for 7 and a half hours. We don't have a tea break. In many places they work on units and minutes. It is the same in manufacturing, the same in the foundry, the same in forging. In my department, let's say the guys in the forge started work at 8 am. Half an hour later you can't go to the restroom. They are immediately questioned, 'Do you have to go to the restroom after half an hour? In order for the worker to go to the toilet, someone has to come and replace his place. If he leaves work and goes, he gets a defense report. It's because the conditions are like this, so it's not just the contract."

While the group collective labor agreement negotiations for the 2019-2021 period with MESS are ongoing, Çimsataş workers staged a protest inside the factory.

One of the workers whose statements are included in the article titled "Çimsataş Resistance from the Words of the Workers” says the following:

"The shortage of food, the shortage of heating in the parts workshop, the dust problem in the foundry, the problem in the changing rooms, the lack of tea breaks, the pressures, the problem of working by the minute. The problem of not being able to go to the toilet... There was already an accumulated reaction against working conditions. Working for low wages added salt to the fire. Add to that the hikes in the prices of basic consumer goods and people are now fed up."

The Fuse of the Strike Is Ignited

Upon hearing that the CLA had been signed, Birleşik Metal-İş Union Anatolia Branch President Deniz Ilgan and workplace representatives made a statement to the night shift workers in the cafeteria. The terms of the agreement met with the opposition of the workers in the factory. Aware of the reaction of the Çimsataş workers, the branch president, together with the workplace representatives, walks around the factory and tries to calm the workers down. Mustafa Yalçın says the following about this:

"The contract was signed in the middle of the night despite all warnings. The branch president was already in the factory at that time. He didn't go to the contract session. He had already been in the factory for a week. The fever of the people in the factory wouldn't go down, and the branch president was trying to lower the fever of the people in the factory."

However, despite the union's efforts, the reaction of the workers did not subside. Eventually, the fuse of the strike is ignited in the forging section. Mustafa Yalçın describes what happened in the cafeteria and the forging section as follows:

"After we went to lunch and came back, they told us that the branch president and representatives were there making a statement about the contract. We had just returned from lunch, then a friend and I went back to the cafeteria. The branch president was making a statement. They said the contract had been signed. People were still reacting when we arrived. They said, 'We will make a collective statement in the morning'. Then we went back to the forging section. When we told them under what conditions the contract had been signed, all the friends there didn't want to work at the same time. Suddenly production stopped at the forging. When the branch president and representatives heard that work had stopped, they came to the forging section. Obviously they calmed down the other departments and came to the forging department. Because everyone is angry. They said that this is not going to happen, we should work. People didn't want to work. We went to the pavilion and sat there. Then the production group manager came. The production group manager said that this was not the way to demand rights, that it had to be done differently. Then, after the 2-hour work stoppage, people went back to work. But the representatives and the branch president promised that when people arrived in the morning there would be a vote for the day shift and the night shift, and then there would be a vote for the 4-12 shift. The branch president left, saying that the union would stand by whatever decision was made, whatever the majority wanted. Then people went back to work."

On the morning of January 12, workers coming out of the night shift and workers entering the day shift gathered in the production department to vote on whether to accept the contract on these terms. Here too, the branch chairman explained the contract and tried to prevent this, despite the fact that the workers strongly expressed their rejection of the contract and showed the will to start a wildcat strike. Mustafa Yalçın says the following about what happened there:

"The branch president said there that the contract was signed. He said that the contract was signed under these conditions. Of course, when there were reactions saying 'Why was this contract signed, we didn't want this contract to be signed in this way, is there nothing for us?' Then the branch president said 'Friends, we already had such a problem during the night shift. We will take a vote. Shall we accept the contract or not?' A corridor was created so that those who agreed could go this way and those who disagreed could go this way. When he said those who did not accept the contract, everyone went to the side of those who did not accept. Then the branch chairman said, “Is there some confusion?” and took another vote. This time people reacted loudly: 'Brother, the vote has been taken. We do not accept this contract. There is no need to vote again. Do it ten times if you want. The same thing will happen again'. As a matter of fact, the vote was held 3 times. All three times the contract was not accepted. There was a group of 450-500 workers, day shift, night shift. 7 people said they accepted the contract. The branch president said we will also seek the opinion of the 16:00-00:00 shift. The night shift workers should go home. Let the day shift go back to work, let's get the opinion of the 16:00-00:00 shift. Let's decide accordingly and determine our demands,' he said."

Çimsataş workers strongly express their rejection of the contract after the union branch chairman insisted on voting on its acceptance

Despite the fact that almost all of the night shift and day shift workers voted in favor of starting the wildcat strike, the branch president delayed the start of the strike by saying that we should also get the opinion of the 16:00-00:00 shift. However, in the vote held in the 16:00-00:00 shift, the workers said that they did not accept the contract and that they could not work like this, and the strike began in this shift as well. In the factory, where a total of 835 workers work, almost all workers in 3 shifts participated in the strike. The demands set by the workers who wanted an additional protocol were as follows:

- A further 35 percent raise on top of the 27 percent agreed in the contract for the first 6 months. For the second 6 months, a raise at the rate of inflation.

- Overtime pay should be set at 100 percent on weekdays and 300 percent on weekends.

- Private health insurance that covers the worker should also cover the family.

- A net 100 percent increase in social benefits.

- Seniority differential, intermediate rest and tea breaks.

- Bank promotions, which have been underpaid for a long time, should be given in full.

- No worker should be dismissed for work stoppage and it should be written in the additional protocol.[54]

Çimsataş workers launch a wildcat strike, express their problems at the workplace and identify their demands

The union branch president tells the workers, "As a branch, we are behind you, we are with you. We will fight here together“. In the evening after the strike began, the company management requested a meeting, but no agreement was reached. On January 13th, workers arriving for the morning shift were prevented from entering the factory. However, the workers took advantage of the opening of the gate during the entry of a riot vehicle into the factory and entered en masse.

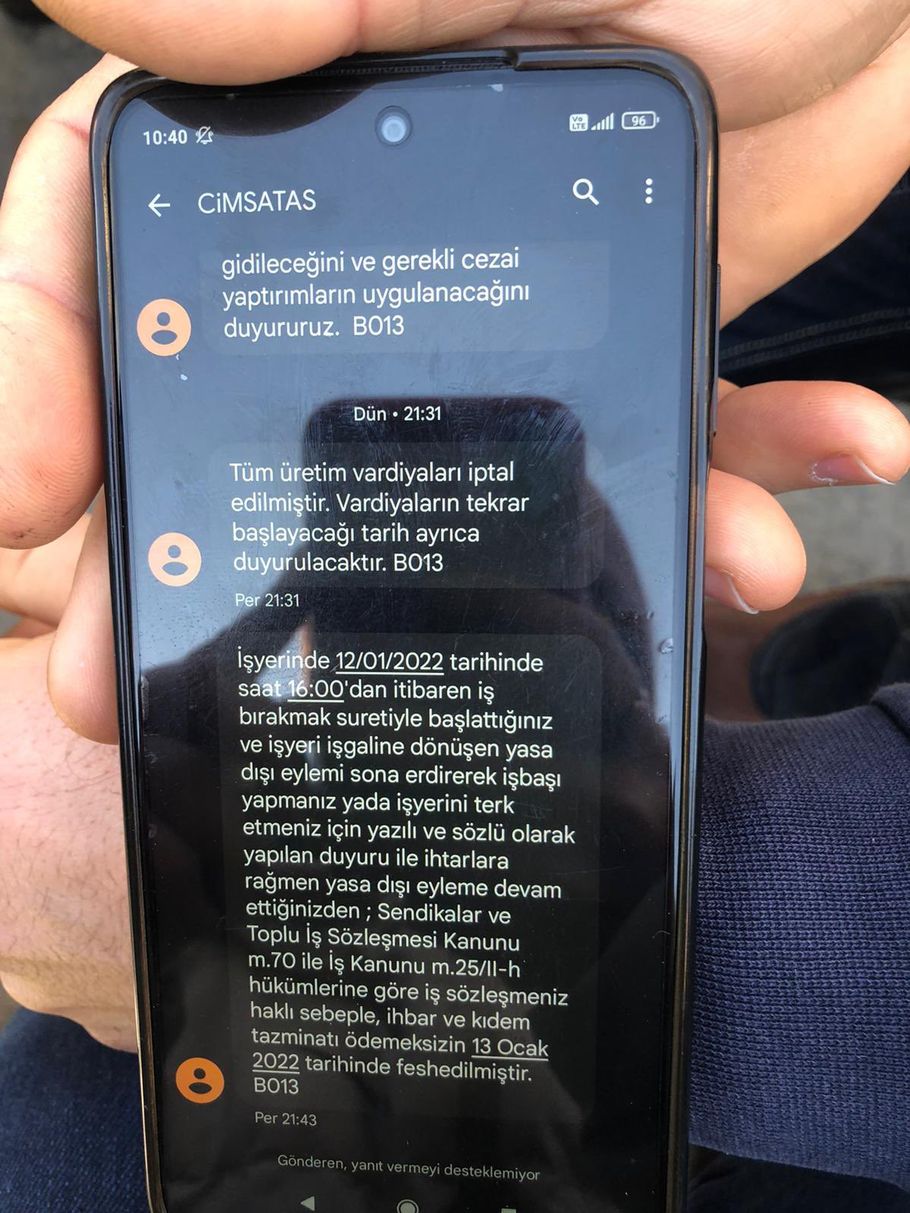

At around 10:00 a.m. on Thursday, 13 January, a message is sent by the company to the workers stating that “due to your illegal action that you started by stopping work at 16:00 on 12.01.2022 and turned into an occupation of the workplace, the damage incurred in our workplace in the amount of 5 million TL per day and any damages that may arise will be compensated from the workers and the necessary penal sanctions will be applied.”[55]

While the workers were waiting inside the factory, a Ministry of Labor inspector arrived, listened to the workers, took a report and left. In the afternoon, Akdeniz District Governor Muhittin Pamuk arrives at the factory and first meets with the workers and asks them about their demands. Later, a meeting was held with the company management under the mediation of the district governor. Soner, one of the workers who attended the meeting, writes the following about what happened there in his article titled "Çimsataş Resistance from the Words of the Workers":

"When the district governor arrived, there was also the lawyer of MESS. ‘Mr. district governor, they got a 70 percent raise,’ he said. We intervened, we said, 'Tell us what 70 percent is according to what? Why don't you tell us why they signed for 27.40. The general manager of Çimsataş said they would make arrangements regarding working conditions. I said, the workers sent us here as spokespersons, give us a bonus of one gross salary, let me go and ask the workers, if they say it's okay, let's end the resistance. The district governor said: "yes, general manager, what do you think, it's a good offer." The lawyer of MESS turned to the general manager and said: “You can't even give them a single pinhead. If you give them a right here, life in the metal sector in Turkey, where there are 243 factories, will come to a standstill, not even the President will be able to get out from under this..."

Mehmet Kurt says the following about the attitude of the union branch president during the meeting:

"Deniz Ilgan, the branch president, was present at the meeting with the district governor. He didn't say that the workers want this or that, that we are right about this or that. He knew Ozan, the lawyer of MESS. He had a friendly chat with him. We explained it there. The district governor also made a round speech there. Then we told the district governor, 'You do your part and we will do our part as workers'."

As a result, the meeting ended without an agreement and TOMAs (riot control vehicles) entered the factory after the district governor left. On January 13th, in the evening, workers inside the factory and in the garden were forcibly removed from the factory by the police. Workers continued to wait in front of the factory after the police intervention.[56] Mustafa Yalçın says the following about what happened during and after their removal from the factory:

"The district governor left. It was evening. He said that the riot police would intervene and that we had to get out of the factory. Of course, we had no bad intentions. We don't want to damage the factory, clash with the police or cause other problems. Our intentions are clear. We are trying to earn a living. So we went outside. But we kept chanting our slogans. At around 8:30 or 9 p.m., everyone went home with the instructions of the branch president to gather there again in the morning. That night I received a message on my phone that my employment contract was terminated."

Workers left the factory on the evening of January 13 and that evening the employment contracts of 13 workers, two of whom were workplace representatives, were terminated with a message sent to their cell phones. The message sent by the employer to the workers reads, “Since you continued the illegal action despite the written and verbal announcements and warnings to end the illegal action that you started at the workplace on 12/01/2022 by stopping work as of 16:00 and turned into an occupation of the workplace and to return to work or to leave the workplace, your employment contract was terminated on 13 January 2022 for just cause, without payment of notice and severance pay, in accordance with Article m. 70 of the Trade Unions and Collective Labour Agreement Law and Article m. 25/II-h of the Labor Law.”[57]

On the morning of Friday, January 14, the workers again gathered in front of the factory in large numbers and continued the strike. However, on that day, the Birleşik Metal-Iş union issued a statement against the wildcat strike launched by the workers, clearly leaving its members alone against the boss. The statement argued that the contract signed with MESS was an achievement and that the strike was damaging this achievement, saying, "Different demands can always come into question in this process. In Mersin ÇİMSATAŞ, it is not possible in terms of the existing group agreement system and union functioning to bring up a new collective labor agreement demand by not recognizing the signed group collective labor agreement. The practices arising from operational reasons and causing victimization of our members will definitely be corrected with the joint struggle of our union and ÇİMSATAŞ workers. The fact that some circles create a different expectation and perception on our members is an effort to pit our members against our union. The manipulations of these circles that harbor animosity towards our union have now reached a level that will cause harm to ÇİMSATAŞ workers. We will not allow this.“[58]

Çimsataş management naturally uses this statement, which declares that the union is on the side of the boss against the workers, to break the workers' strike. The company management sent a message to the workers around 16:30 on the same day, sharing the union's statement. The message emphasized the statements in the leaflet, such as that the strike was not supported by the union, that different expectations were wanted to be created on union members, and that the union was pitted against its members.[59]

Mehmet Kurt, the chief workplace representative, said that Deniz Ilgan, the head of the Anatolian branch of the Birleşik Metal-İş Union, who had been in front of the factory until then, was nowhere to be seen after this message:

"He posted an article on the Birleşik Metal page saying that he was not with the resistance. Everyone who is affiliated to Birleşik Metal has already seen this. The employer cut a certain part of the message and sent it to us. Deniz Ilgan, the head of the Anatolian branch, also posted this as a message on his page. On Friday, after the branch president posted it on his page. He ran away. We never saw him again."

Despite the union's stance, the layoffs and the moves of Çimsataş management, the strike continued on Saturday, January 15. At noon on January 15, Mehmet Kurt, who was also one of the dismissed workers, addressed the workers in front of the factory and told them that they were going to have a meeting with the company, that the negotiations would be conducted through four representatives, and that the other workers should go home.[60] As a result of the meeting between the employer and union representatives, while other demands were not accepted, it was announced that the physical conditions would be improved, an improvement commission would be established, and the dismissed workers would not be reinstated but would be paid their severance pay.[61] Thus, the strike at Çimsataş ended without any gains and the workers returned to work on Monday, January 17.

Results

The following words of Mustafa Yalçın summarise all that has happened:

“Birleşik Metal publishes a text. It sends this to us through the employer. This comes through a message. In other words, the union and the employer got together, and they send messages to divide people and get them back to work. I and many people working in this factory know that Birleşik Metal is a union affiliated to DİSK. Birleşik Metal has 7000-8000 members. There are dues coming from here. Türk Metal has 120.000 members. There are dues coming from them. Çelik-İş has members, there are dues from them. The unions have sliced such a cake for themselves, everyone got their share.”

Indeed, this strike has once again shown that the three unions, which have signed the same group collective labour agreement with MESS for years, are no different from each other, and that they are in fact just different teeth on the same gear. Birleşik Metal-İş, which says that it is strifeful and whose executives always rage in meetings, was not content with taking a passive attitude in the face of the wildcat strike of the workers, but openly engaged in strike-breaking by publishing a statement that tried to market miserable conditions as gains and slandered the strike of the workers.

Despite having a strong unity within itself and a certain experience of struggle, despite showing the will to initiate a wildcat strike with a joint decision and to continue it for four days with almost full participation, the strike of Çimsataş workers ended with the lay-off of 13 workers and without any gains due to the pressure and siege of the boss, the police and the union. One of the main reasons why the strike ended without any gains is the fact that Çimsataş is part of MESS. For the reasons we have explained above, the group collective bargaining system in MESS-owned workplaces limits the ability of workplaces to act on their own and reduces the possibility of individual gains, especially for workers in medium and small workplaces. The words of the MESS lawyer during the meeting, ‘If you give a right here, life will stop in the metal sector where there are 243 factories in Turkey, even the President would not be able to get out from under this’, is an expression of the fact that the bosses in the metal sector, where there is a tradition of class struggle, are aware that they have to act organised against the workers. In the face of this organisation, workers will only be able to achieve gains through militant, strong and widespread struggles by acting in unity that goes beyond the unions. In the year 2015, the reason why a significant part of the wildcat strikes in the factories where Türk Metal-İş was authorised were able to achieve partial gains despite negative factors such as organisation and experience in the workplaces being insufficient, lack of unity and coordination among the workplaces, is that they took place in a large number of workplaces. As for the strike of Çimsataş workers, it did not spread to other workplaces within the scope of MESS, including the workplaces where Birleşik Metal-İş is authorised, and was isolated. On the other hand, although some small unions and political organisations showed solidarity at various levels, some official left-wing organisations did not support the Çimsataş strike due to their direct and indirect relations of interest with DİSK and Birleşik Metal-İş. For example, after the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) MYK (Central Executive Committee) member Alparsan Savaş, who is also a specialist in Birleşik Metal-İş, directly shared the text written by Birleşik Metal-İş against the workers' strike on social media, many comments and criticisms were made that TKP was not on the side of Çimsataş workers.[62]

However, although there were no practical gains in terms of the demands of the Çimsataş workers and 13 workers were laid off, for the working class as a whole, the acquisition of these lessons is a gain in itself. With these experiences, the working class of Turkey, especially the metal workers, each time better understands the role of unions, what to do next time, what not to do, who to trust and who not to trust. In this respect, the 2022 Çimsataş strike, which is one of the most important strikes in the January-February 2022 strike wave, as it took place in an important factory where 835 workers work and mass production is carried out, has also taken its place in the history of the struggle of metal workers.

Trade Union Struggle, Capital Accumulation, MESS and Koç Holding in Turkey - Özgür Öztürk (Praksis Issue 19) https://www.praksis.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/19-Ozturk.pdf

According to the Regulation on Branches of Labour of Trade Unions published in the Official Gazette dated 11.8.1964, ‘All kinds of metal manufacturing’ was defined as a single branch of labour covering mining and steel industry, manufacture of metal goods, manufacture of machinery, manufacture and repair of electrical machinery and apparatus and tools, manufacture and repair of metal transport vehicles, manufacture of other metal goods and materials. On 17.10.1971, in the new Regulation on Branches of Labour, which was published in the Official Gazette dated 17.10.1971, mining and metal were determined as separate branches of labour. https://www.tekgida.org.tr/turkiyede-iskollari-duzenlemesi-1947-1980-58902/

2015 Demonstrations of Türk-Metal Member Workers, p. 320, 321

The unions Otomobil-İş and Maden-İş merged in 1993 to form the Birleşik Metal-İş union.

With the decision taken at the 14th Ordinary General Assembly held on 13-14 October 2018, the short name of the union “ÇELİK-İŞ SENDİKASI” was changed to “ÖZÇELİK-İŞ SENDİKASI”.

By Article 197 of the Delegated Legislative Decree No. 700 dated 2/7/2018, the phrase ‘Council of Ministers’ in this paragraph has been amended as ‘President of the Republic’.

Tradition and Future 40 Years of MESS, Vol. 1, p. 148-150, BZD Yayıncılık

MESS Strikes (1977–1980) - Can Şafak, p. 21-28 (https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2576025)

ibid, p. 35,36

ibid, p. 37-39

Issues of Hürriyet, Cumhuriyet, Milliyet, Radikal newspapers dated 19.09.1998

Issues of Cumhuriyet, Gündem, Radikal newspapers dated 22.09.1998

Compiled from Hürriyet, Milliyet, Radikal, Cumhuriyet, Gündem, Radikal, Birgün and Sol newspapers.

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, Yazılama Yayınevi, sf. 310

Ve Şaltere Uzandı Nasırlı El, Yıldırım Doğan, sf. 31

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 314

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 315

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 317

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 318

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 320

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 324, 325

Emeğin Yıllığı 2015, p. 366

Before the strike of Birleşik Metal-İş on 29 January 2015, the bosses of Delphi and Mahle in Izmir, Bekaert in Kocaeli, Alstom and Schneider Enerji in Gebze, Schneider Elektrik in Manisa and ABB in Istanbul, who were caught unprepared for this situation, left MESS and signed 2-year contracts, of which ABB, Alstom, Schneider Enerji and Schneider Elektrik later established EMİS. However, EMİS member bosses became members of MESS again in 2020.